The First Commandment: No Other Gods

We come now to our exposition of the Ten Commandments.[1] Following the Westminster Larger Catechism, we can divide them into one group of four, pertaining to “our duty to God,” and a group of six, describing “our duty to man.”[2] So the structure of the Decalogue parallels Jesus’ “two great commandments,” to love God and to love one’s neighbor (Matt. 22:36–40). This is something of a rough-and-ready distinction, however, since the last six commandments certainly describe duties to God as well as to man, and since the first four have implications for our conduct toward other people as well as toward God.[3] As I indicated in chapter 22, the law is a unity.

My discussions of the commandments will move, as a rule, from theological background to specific applications, from narrow meanings to broad meanings (see chapter 22), from positive to negative.

The first commandment reads simply, “You shall have no other gods before me.” Confessional expositions have been as concise as that of Luther’s Small Catechism: “We must fear, love, and trust God more than anything else.”[4] And they have been as elaborate as this from the WLC:

Q. 104. What are the duties required in the first commandment?

A. The duties required in the first commandment are, the knowing and acknowledging of God to be the only true God, and our God; and to worship and glorify him accordingly, by thinking, meditating, remembering, highly esteeming, honoring, adoring, choosing, loving, desiring, fearing of him; believing him; trusting, hoping, delighting, rejoicing in him; being zealous for him; calling upon him, giving all praise and thanks, and yielding all obedience and submission to him with the whole man; being careful in all things to please him, and sorrowful when in anything he is offended; and walking humbly with him.

Q. 105. What are the sins forbidden in the first commandment?

A. The sins forbidden in the first commandment are, atheism, in denying or not having a God; idolatry, in having or worshiping more gods than one, or any with or instead of the true God; the not having and avouching him for God, and our God; the omission or neglect of anything due to him, required in this commandment; ignorance, forgetfulness, misapprehensions, false opinions, unworthy and wicked thoughts of him; bold and curious searching into his secrets; all profaneness, hatred of God; self-love, self-seeking, and all other inordinate and immoderate setting of our mind, will, or affections upon other things, and taking them off from him in whole or in part; vain credulity, unbelief, heresy, misbelief, distrust, despair, incorrigibleness, and insensibleness under judgments, hardness of heart, pride, presumption, carnal security, tempting of God; using unlawful means, and trusting in lawful means; carnal delights and joys; corrupt, blind, and indiscreet zeal; lukewarmness, and deadness in the things of God; estranging ourselves, and apostatizing from God; praying, or giving any religious worship, to saints, angels, or any other creatures; all compacts and consulting with the devil, and hearkening to his suggestions; making men the lords of our faith and conscience; slighting and despising God and his commands; resisting and grieving of his Spirit, discontent and impatience at his dispensations, charging him foolishly for the evils he inflicts on us; and ascribing the praise of any good we either are, have, or can do, to fortune, idols, ourselves, or any other creature.[5]

Both Luther and the Larger Catechism find in the first commandment an issue of the heart. For both, the commandment does not tell us only to avoid worshiping other gods, like Baal, Moloch, Chemosh, Astarte, Zeus, Hera, Apollo, and so on. It also teaches us to avoid placing anything other than the true God ahead of him in our thoughts, actions, and affections. The forbidding of literal polytheism is the “narrow” meaning of this command (chapter 22). The forbidding of any competition at all with the true God for our allegiance, obedience, and affection is the broader meaning. As with all biblical ethics, the first commandment is a matter of lordship. We are to recognize from the heart that God is Lord of all things and that therefore he will tolerate no rivals.

The difference between Luther’s exposition and that of the Larger Catechism is that the latter tries to enumerate, as exhaustively as possible, the attitudes of heart and the physical actions that are appropriate to this command and the would-be rivals of God that tempt us to violate it. I find the long lists of virtues and sins in the Larger Catechism amusing at times. I can almost picture a committee sitting around a table, with various people putting up their hands to inject this or that item (“Oh, we must not forget ‘highly esteeming’!”), leading to a list of gargantuan proportions and literary disaster. The Heidelberg Catechism, as usual, is far more graceful:

Q. 94. What does God require in the first Commandment?

A. That, on peril of my soul’s salvation, I avoid and flee all idolatry, sorcery, enchantments, invocation of saints or of other creatures; and that I rightly acknowledge the only true God, trust in Him alone, with all humility and patience expect all good from Him only, and love, fear and honor Him with my whole heart; so as rather to renounce all creatures than to do the least thing against His will.

In this catechism, there is also a list, but it makes no attempt to be exhaustive, and the first person language (echoing the second person, singular language of the Decalogue itself), along with the rhetorically powerful final clause, engages the heart as well as the mind. The Larger Catechism also tries to engage the heart, but it always seems to have in mind the model of a legal document, multiplying citations as if to close every loophole. The Larger Catechism wants to ensure that “having another god before me” will be illegal in the church, and that nobody will have any excuse.

Nevertheless, I actually find the Larger Catechism more edifying than the Heidelberg Catechism, because of its breadth and depth. Whatever we may think of the long lists, the items are almost always biblical (I have chosen not to list the proof texts), and they enable us to dig deeply into the nature of our exclusive allegiance to the Lord. Did it occur to you that “lukewarmness” was a violation of the first commandment?[6] It didn’t occur to me, either, before reading it here. But when you think about it, that correlation is a profound insight. To the extent that we are lukewarm in our attitude toward God, we are putting other things ahead of him. Like other Bible passages (see chapter 21), the first commandment makes demands upon our emotional life. So for those who have the patience to actually meditate on the lists of the Larger Catechism and compare each item with Scripture, there is great spiritual profit here.

Note also little touches like the opening of Answer 104, where we are urged to recognize God as “the only true God, and our God” (emphasis added). That picks up the language of Exodus 20:2, where God identifies himself as “the Lord your God.” This language excludes any merely theoretical acknowledgment of God’s existence. This confession, as much as that of the Heidelberg, is a personal confession, one of covenant allegiance. The Larger Catechism repeats that point in Answer 105, where atheism is either denying (the existence of) God or “not having a God.” So an atheist may be someone who believes that God exists, but who refuses to be his covenant servant.

The lists show us, in practice, what it means to interpret the Decalogue according to the principles of WLC, 99, which I discussed in chapter 22. In the lists, the Larger Catechism considers how each commandment “requires the utmost perfection of every duty” and “forbids the least degree of every sin” (rule 1). The lists also show the “spirituality of the law,” how it extends to “understanding, will, and affections,” and also to “words, works, and gestures” (rule 2). And they show how each prohibition also forbids all “causes, means, occasions, and appearances thereof, and provocations thereunto” (rule 6). In the end, they show that each commandment commands all righteousness and forbids all sin. If you or I can measure up to the standards of WLC, 104 and 105 (and of course we will not measure up, short of glory), then we will be completely sinless. For one who is not disloyal to God in any way, in any degree, will surely not do anything contrary to his will. All sin is disloyalty to God. All sin is putting something else before him. So the first commandment defines all sin and all righteousness, from its particular perspective of covenant loyalty.

LOVE

The Larger Catechism makes a huge number of connections between the first commandment and various virtues and sins. In what follows, I will focus on some of the more obvious virtues implied by the first commandment, perhaps adding some structure and organization to the lists in the Catechism. I shall thereby try to show that the Catechism’s perspective is warranted by Scripture itself, for it summarizes the ways in which Scripture applies this commandment to our ethical life.

In chapters 3 and 22, I described the suzerainty treaty as an ancient Near Eastern literary form, of which the Decalogue and the book of Deuteronomy are examples. In the secular treaties, following the name of the great king and the historical prologue, came the stipulations. The first stipulation, typically, was the requirement of exclusive loyalty. The vassal is not to make similar treaties with any other king. In Exodus 20:3, the first commandment makes that same requirement of Israel. Israel is not to give its ultimate loyalty to any other god.

In the secular treaties, such exclusive covenant loyalty was sometimes called love. Deuteronomy 6:4–5 also expresses covenant loyalty in the language of love: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might.” This is, of course, Jesus’ first great commandment (Matt. 22:36–38). This loyalty-love is the center of the believer’s relationship with God.

I discussed the nature of love in chapters 12 and 19, so I won’t say much more at this point, except to reiterate that in the Decalogue, as well as in the rest of the Bible, love is central to the lives of God’s people. It summarizes our entire obligation.

In the context of the Decalogue, this law of love follows the historical prologue (“who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery”), so we see that grace precedes obedience, and that love is the first response of a person whom God has redeemed. And the command to love God precedes the other commandments, indicating that love is the motivation for keeping the rest of the law.

The New Testament realization of this commandment is that Jesus demands the same exclusive covenant loyalty that the Lord demands in the Decalogue. Jesus says that loyalty to him is a higher obligation than loyalty to our parents (Matt. 10:34–37). He did defend the fifth commandment as well, charging that the scribes and Pharisees did not honor their parents (Mark 7:9–13), but he nevertheless placed himself ahead of parents in our hierarchy of ethical obligations. But who deserves a loyalty higher than our parents except the Lord himself?

Jesus should be more important to us than our own lives (Matt. 16:24–27). Indeed, Paul says, “But whatever gain I had, I counted as loss for the sake of Christ. Indeed, I count everything as loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things and count them as rubbish, in order that I may gain Christ” (Phil. 3:7–8). None of this makes any sense unless Jesus is indeed God. As God demanded exclusive covenant loyalty of Israel under Moses, so Jesus demands no less from us in the new covenant.

When the rich young ruler asked Jesus what he should do to attain eternal life, Jesus mentioned several commandments of the Decalogue. He mentioned only commandments from “the second table,” the commandments emphasizing our responsibility to our fellow man. When the ruler asked, “What do I still lack?” the reader might expect that Jesus would cite the first table, our responsibility to God. Instead, Jesus said, “If you would be perfect, go, sell what you possess and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me” (Matt. 19:21). Jesus here demanded a radical renunciation of the ruler’s besetting sin, coveting wealth. And, in effect, he replaced the first table of the law with the commandment to follow him. To be perfect, we must be exclusively loyal, not only to God, but specifically to Jesus. Exclusive loyalty to Jesus does not detract from exclusive loyalty to God, only because Jesus is God.

So the first commandment of the Decalogue is first of all a demand for exclusive loyalty to God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—which is another way of stating the law of love.

WORSHIP

Another way to look at the first commandment is to say that it is about worship. The first four commandments deal especially with our relationship to God. But in all our relationships to God, we stand as worshipers. When people meet God in the Bible, they bow down; they are moved to worship. So the first four commandments serve as rules for worship. The first commandment deals with the object of worship, the second with the manner of worship, the third with the language of worship, and the fourth with the time of worship.

People who take courses on ethics usually don’t expect to have to study worship as well. Students usually like to focus on second-table issues like abortion, war, and divorce. But in a Christian ethic, we must focus also on our duty to God. Indeed, that must be our primary focus. And the term worship is shorthand for “our duty to God.”

In Scripture, worship is both a broad concept and a narrow concept. Narrowly, worship is what we do on certain occasions. In the Old Testament, it includes the offering of sacrifices of animals, flour, oil, and wine. In both testaments, it includes meetings for prayer, praise, the reading and teaching of Scripture, and observing sacraments. The people of God carry out similar activities in families and privately. The word cultic is sometimes used to describe such activities.[7] The first commandment requires, of course, that such worship be given only to the one true God.[8]

Remarkably, however, Jesus also accepts worship from human beings (Matt. 28:9, 17; John 9:35–38), and he demands that we honor him as we honor the Father (John 5:23). Even the angels worship him (Heb. 1:6). One day all will bow before the name of Jesus (Phil. 2:10). The hymns of Revelation are directed to him (Rev. 5:11–12; 7:10).[9] So first-commandment language applies to the worship of Jesus: his is the only name on which we should call for salvation (John 14:6; Acts 4:12). As the Lord is our exclusive object of worship, so is Jesus, rendering an identity between the two inevitable. As we are to love Jesus above all others, so we are to worship him as we worship God.

Worship in Scripture also has a broader meaning, as indicated in Romans 12:1–2:

I appeal to you therefore, brothers, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship. Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.

Here the “living sacrifice,” the “spiritual worship,” is to live lives in the world that are transformed by God’s Spirit. Here, worship is ethics. In the Old Testament, too, there was a close relationship between worship and purity of life. One could approach God only with “clean hands and a pure heart” (Ps. 24:4; cf. Luke 1:74; Acts 24:16; 2 Tim. 1:3). When we come before God, he must deal with our sins. Hence, Old Testament worship emphasizes sacrifice, and New Testament worship celebrates the finished sacrifice of Christ.

The biblical vocabulary of worship (as ‘abad, latreuein, douleuein, leitour-gein) uses terminology that can refer either to secular or to religious service. And cultic language often applies to ethical purity in general (Matt. 6:24; James 1:27; Heb. 12:28). Paul uses such language also in connection with his mission to the Gentiles. “For God is my witness,” he says, “whom I serve (latreuein) with my spirit in the gospel of his Son” (Rom. 1:9). In Philippians 2:17, he says, “Even if I am to be poured out as a drink offering upon the sacrificial offering of your faith, I am glad and rejoice with you all.”

I shall therefore distinguish between worship in the broad sense and worship in the narrow sense. In the broad sense, worship is a perspective on all of biblical ethics. To worship is to obey God, and vice versa. All of life is worship, an offering to him, the living sacrifice of our body. Thinking of our lives in that way is a motivation to godly behavior. And this image shows us again how all sin violates the First Commandment, and how all righteous actions fulfill it.

CONSECRATION

Consecration is an aspect of worship—setting ourselves and all our possessions apart for God’s use. In a sense, all worship is consecration and vice versa, so consecration is another perspective on the first commandment and on the Christian life as a whole.

Note the many laws in the Pentateuch requiring the sanctification of individuals and things: the firstborn child (Ex. 13), the ransom of individuals for the census (Ex. 30:11–17), the consecration of the Nazirite (Num. 6:1–21), the consecration of firstfruits (Deut. 26:1–19). In circumcision (Gen. 17:9–14; Lev. 12:3) and the Passover (Ex. 12; Num. 9; Deut. 16), God’s people recognize that he has set them apart (consecrated them) from other nations and made them his “holy” people (Lev. 20:26; Deut. 7:6; 14:2, 21; etc.). Similarly, when a person is baptized, he takes upon himself the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit (Matt. 28:19): he becomes God’s person, distinguished from all the other families of the earth. And the Lord’s Supper signs and seals the new covenant in Jesus’ blood, by which we are separated from the world (Matt. 26:28; 1 Cor. 11:25).

So God separates his people from the world to be distinctly his. In covenant, he is our God and we are his people. We have seen in previous sections of this chapter that the first commandment is grounded in who God is, as the Creator, in contrast to us, as creatures. By the fact of our creation, we are bound to love, serve, and worship God above all others. But our obligation is also grounded in what God has done in history, namely, his redemption (Ex. 20:2) and his choice of us as his people, taking us from all the other nations to be holy in him. He is our Lord by creation and redemption.

SEPARATION

In discussing love, worship, and consecration, I have linked the first commandment to three positive biblical concepts.[10] But the language of the commandment itself, like most of the commands of the Decalogue, is negative: “You shall have no other gods before me.” So we should look also at the negative thrust of the commandment.

Why is the Decalogue so largely negative? All of the commandments except the fourth and fifth are stated as prohibitions, and the fourth contains much negative language. It is, of course, a matter of emphasis. As we have seen (and as the Catechism emphasizes), negative formulations do not rule out positive paraphrases and applications. Positive and negative are matters more of phrasing than of meaning. But why all the negative phrasing?

The very notion of exclusive covenant loyalty requires us to refuse rival loyalties. And there are rivals, others who tempt us to abandon our covenant with God.[11] God has made covenant with us in a fallen world. So the negative focus reflects the reality of sin and temptation. Obedience to God in a fallen world always involves saying no—to Satan, the world, and our own lusts (1 John 2:15–16). And it requires us to take up arms against wickedness (Eph. 6:10–20). So the ethical life is a conflict, a battle. Scripture calls us to repentance (turning away from a sinful course), self-denial (taking up our cross to follow Christ), and separation (breaking away from associations that compromise our loyalty to God). The New Testament in this regard is no less negative than the Old Testament, the Sermon on the Mount being a case in point. And even love, that most positive of virtues, is described negatively in 1 Corinthians 13.

There is a strong tendency in modern evangelicalism to stick to the positive and avoid the negative. We can argue about the rhetorical issues, but we should be reminded that Scripture, God’s own communication to us, often stresses the negative. Sometimes we need rebuke; we need to be told no. Sometimes we need to reject false doctrine because it is false. Sometimes we must present God’s standards in contrast to the standards of the world, if they are even to be understood.

So the first commandment implies a doctrine of separation, of exclusion, of denial. It tells us to say no. From what are we called to separate? Here, as in all matters, Scripture is our sufficient guide. The concept of separation has been prominent in evangelical writings about the Christian life. Such writings have described “the separated life” as one without alcohol, tobacco, dancing, card playing, and so forth. I shall say more about these issues, but for now we should note that such things are not the focus of biblical separation. Scripture itself focuses, rather, on separation from the following:

False Gods

The narrow teaching of the commandment is that we should not worship beings other than Yahweh (cf. Deut. 6:13–15; 12:29–32). Scripture mentions many such beings that demand and receive worship from humans: Baal, Astarte, Moloch, Chemosh, Dagon, Rimmon, etc. These gods may be fictions, or they may be supernatural beings (demons, 1 Cor. 10:20) who wrongly claim the prerogatives of Yahweh. When tempting Jesus, Satan himself demands worship, and Jesus rebukes him by quoting Deuteronomy 6:13, which reflects the first commandment (Matt. 4:9–10).[12]

God tells Israel to be literally iconoclastic, to break down the pillars and altars of false gods, to destroy every vestige of Canaanite religion (Ex. 23:24; 34:13; Deut. 12:2–3). Israel’s separation from false worship is to be drastic, radical, and complete.

If exclusive covenant loyalty-love is the root of all righteousness, then to give that love to someone else is the root of all sin. The true God is a jealous God, as the second commandment tells us, and he will not give his glory to someone else (Isa. 42:8; 48:11). As the unfaithfulness of adultery betrays a marriage, so false worship violates the covenant at its heart. Thus, Scripture often draws parallels between adultery and idolatry (Lev. 20:5; Jer. 3:9; Ezek. 16; Hos. 1–4) and between faithfulness in marriage and faithfulness to the Lord (Eph. 5:22–33).

God-Substitutes

Worship of Baal and Astarte violates the narrow meaning of the first commandment. But the command also has a broader meaning. It is wrong also to worship our own power (Hab. 1:11), money (Job 31:24; Matt. 6:24), possessions (Luke 12:16–21; Col. 3:5), politics (Dan. 2:21), pleasure and entertainment (2 Tim. 3:4), food (Phil. 3:19), or self (Deut. 8:17; Dan. 4:30). Surely, if it is wrong to worship Baal, it is also wrong to worship something that is even less than Baal pretends to be. And yet that is what we often do. People who would never dream of bowing down in an idol’s temple put other things ahead of God in their lives. Here the temptation is more subtle, and the rationalizations are more readily at hand. Often we just slip into these patterns, rather than making a conscious decision. So the Bible warns us, using language inspired by the first commandment.[13]

Practices of False Religions

God’s people must abstain from divination, sorcery, necromancy, human sacrifice, and superstitions (Lev. 18:21–30; 19:26, 31; 20:6, 27; Deut. 16:21; 18:9–14). Only the true God knows the future, and he is the only one to whom the believer should turn for supernatural help.

False Prophets and Religious Figures

The Old Testament provides the death penalty for sorcerers (Ex. 22:18), those who tempt Israelites to worship other gods (Deut. 13), and false prophets (Deut. 18). If a city in Israel becomes a center for false worship, other Israelites must make war against that city and destroy it completely (Deut. 13:12–18). False prophets include both those who speak in the name of other gods and those who falsely claim to speak the words of the true God (Deut. 18:20). God’s people are not to give heed to such (Deut. 18:14), but only to the word of God (Deut. 18:18–19).

The death penalties here must be understood in the context of Israel’s unique status as God’s covenant people, in his holy land, with his holy presence dwelling among them. Vern Poythress argues that the destruction of an idolatrous city in Deuteronomy 13:12–18 is in effect part of the holy war of Israel against the Canaanite cities in the time of Joshua.[14] When Israelites behave like Canaanites, they must be treated like Canaanites. But Deuteronomy 20 distinguishes between Israel’s wars against cities within the Promised Land and its wars with cities outside. So the issue in these passages is not idolatry per se, but idolatry within the precincts of God’s holy presence. We should not assume, therefore, that the death penalty should be applied to all idolaters everywhere or in our modern nations. Nor is the radical iconoclasm that God demanded of Israel normative for new covenant believers.

Nevertheless, the death penalties indicate even to us today that idolatry is serious business, and that we should be concerned not only with false religion, but also with people who practice it, lest they influence us to be unfaithful to the Lord (Ex. 23:31–33; Deut. 13:6–8; Josh. 23:7–8; Ezra 4:1–3). That God’s people should shun false prophecy and false teaching is also a New Testament principle. Jesus tells us to beware of false prophets (Matt. 7:15; cf. 24:11, 24), and the apostles oppose them (Acts 13:6–12; 2 Cor. 11:13; 2 Tim. 3:1–9; 2 Peter 2:1–22; 1 John 4:1; Rev. 16:13).

Unholiness and Uncleanness

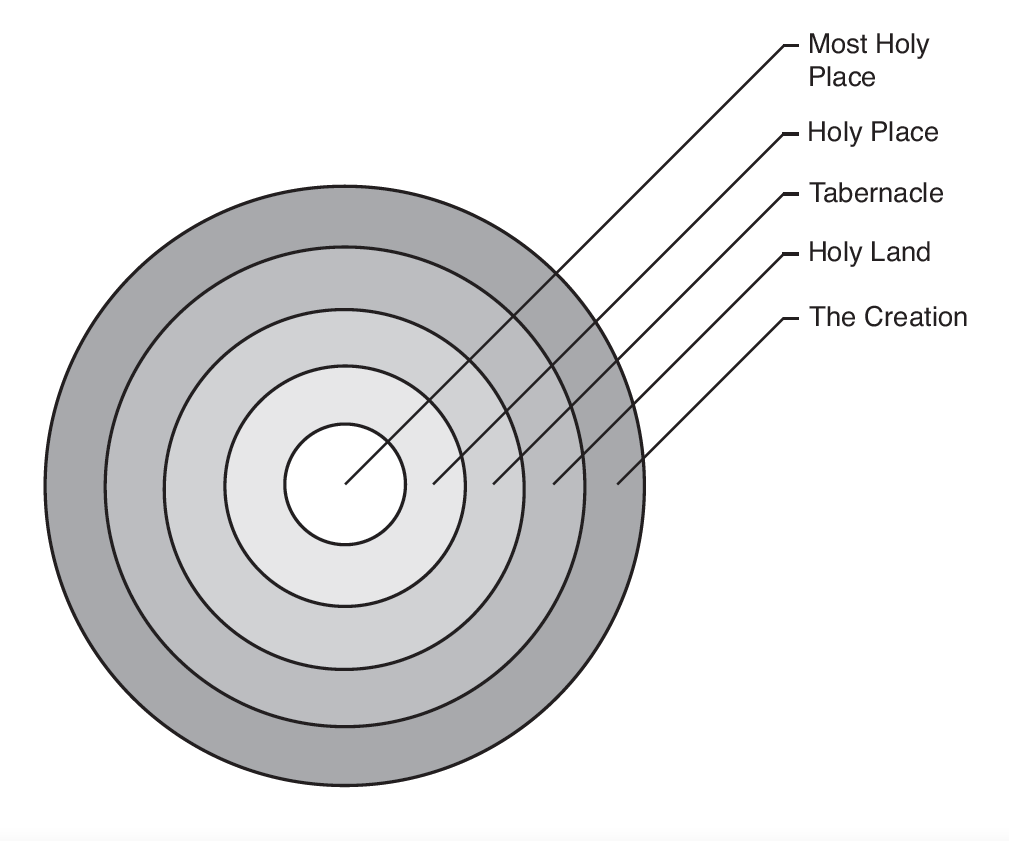

The objects of Israel’s world were divided into three categories: holy, clean, and unclean. The tabernacle, the temple, and the furniture of these buildings are holy. Cattle are clean animals, suitable for food, but pigs are unclean. God intended his people to give special reverence to holy things and to avoid unclean things.

Fig. 6. Degrees of Holiness

God himself is supremely holy,[15] and holy things are things that have a special relationship to God. The tabernacle, God’s house, is holy, but its holiness admits of degrees. The innermost room is the Most Holy Place, entered through another room called merely the Holy Place (Ex. 26:33–34). Compared to the Most Holy Place, the Holy Place is common (the usual opposite of holy). Compared to the Holy Place, the rest of the tabernacle is common. But compared to the area outside, the whole tabernacle is holy. There is even a sense in which the whole Promised Land is holy (Zech. 2:12), the place that God has chosen for his name to dwell in. And in a still broader sense, the whole creation is holy (see fig. 6). The Lord says, “Heaven is my throne, and the earth is my footstool” (Isa. 66:1), relativizing the value of any temple that men might build for him.

The priests are holy people, with holy garments (Ex. 29:29). But, in a broader sense, the whole nation of Israel is holy. God’s own people, separated from all the other nations, are to be “a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Ex. 19:6). They perform holy actions, primarily the sacrificial offerings given to the Lord.

Certain times are holy: the Sabbath and the feasts of the Lord. So, as Tremper Longman points out, God gives to Israel holy places, holy times, holy people, and holy events.[16] The opposite of holy is profane or common, and these terms also admit of degrees. Compared to the Most Holy Place, the Holy Place is common; compared to the Holy Place, the rest of the tabernacle is common, and so forth. God does not tell Israel to avoid the profane or common. Such a prohibition would take Israel out of the world entirely. But he does urge Israel to distinguish between the holy and the common, as between the clean and the unclean (Lev. 10:10).

God revealed to Israel distinctions between clean and unclean things, animals, and people (e.g., Num. 19; Deut. 23:1–14). Poythress believes that cleanness has to do with God’s righteousness and orderliness, and with his desire to illustrate to Israel the importance of separation from sin and death:

Dead bodies are unclean both because of the immediate connection with death and because they degrade the order of living things back to the relative disorder of the nonliving earth. Birds that feed on carrion (dead bodies) are unclean. Things that are somehow defective or deviate from a paradigmatic order are also unclean. Fish with scales are the paradigmatic form of water creature; hence, all water creatures without scales or fins are deviant and unclean.[17]

He subsequently discusses other instances of holiness, cleanness, and uncleanness. These laws do seem to have some connection with hygiene. Many of them mandate practices that modern medical science recognizes as conducive to good health. This may be one means by which God fulfilled his promise to deliver Israel from “the evil diseases of Egypt” (Deut. 7:15; cf. 28:60–61). It shouldn’t surprise us that obeying God tends toward life, rather than toward death. But, Poythress adds, the context of the laws themselves

says nothing about hygiene but stresses the need of Israel to “be holy, because I, the Lord your God, am holy” (Lev. 19:2). The entire system is a pervasive expression of the orderliness and separation required of a people who have fellowship with God the Holy One, the Creator of all order. As Gordon Wenham says, “Theology, not hygiene, is the reason for this provision.”[18]

The language of clean and unclean can also take on a broadly ethical meaning. Psalm 24:3–4 reads, “Who shall ascend the hill of the Lord? And who shall stand in his holy place? He who has clean hands and a pure heart, who does not lift up his soul to what is false and does not swear deceitfully.” Here it is difficult to tell where the ceremonial ends and the ethical begins, but both are certainly present.

The broadly ethical meaning is prominent in the New Testament. God has cleansed the Gentile nations by the grace of Christ, so that they may enter the covenant people on the same terms as the Jews (Acts 10:15; 11:9). In teaching this lesson to Peter, God tells him in a dream to kill and eat unclean animals. In the Old Testament, the pagan nations were the paradigm of uncleanness. God wanted Israel to be separate from them. But in the New Testament, the grace of God abounds to send Christians out to the nations, taking the gospel to them (Matt. 28:19–20). Association with pagans is now mandatory, not discouraged.

In the Old Testament, the assumption was that association with pagans would lead Israel into sin (see Ex. 23:33). Indeed, God instructed Israel to annihilate the Canaanite tribes within the Holy Land (Deut. 7:1–4, 16–26). In the New Testament, however, the assumption is that the power of the gospel will lead pagans into the worship of the true God and Jesus his Son. Even in a marriage between a believer and an unbeliever, God encourages us to hope that the believer’s faith will prevail (1 Cor. 7:12–16; 1 Peter 3:1–6). This doesn’t always happen, but God often works this way, and we are encouraged to pray for this result. As I mentioned earlier, Christians are to shun false teachers, as in the Old Testament. But the fullness of grace in the new covenant gives us freedom from fear and anxiety about the power of Satan.

So, in one sense, God through Christ has cleansed the nations: not that every pagan will be saved, but that the power of Satan to deceive the nations has been so weakened (Rev. 20:3) that paganism is no match for the power of the gospel, and Christians should seek to become fully involved in the lives of pagans, without participating in their sin. And if the nations themselves are now clean, then there is no need to continue the system of clean and unclean objects. So Jesus teaches his disciples that food cannot defile them, and Mark adds, “Thus he declared all foods clean” (Mark 7:19; cf. v. 15; Acts 10:15; Rom. 14:14, 20).

So, in the New Testament, cleanliness (or purity) is ethical, as in 2 Corinthians 7:1, “Since we have these promises, beloved, let us cleanse ourselves from every defilement of body and spirit, bringing holiness to completion in the fear of God” (cf. Eph. 5:5; Col. 3:5).

Holiness and cleanness, then, follow the larger pattern in the biblical applications of the first commandment. Narrowly, they describe the ceremonial requirements for living in the place of God’s special presence. Broadly, they describe our overall ethical relationship to God. The former symbolize the latter, and they also apply the latter to Israel’s unique role in the history of redemption. When the new covenant sets aside that unique role, fulfilling and setting aside the Holy Land, the temple, and the Aaronic priesthood, the ceremonial requirements change. But in the broader sense, we are still in the presence of God, wherever we are in the world, for heaven is his throne and earth is his footstool. And, in his broader presence, it is still important that we have clean hands and a pure heart, that we be separate from the defilements of sin, and that we be holy, as he is holy.

John Frame is the author of many books, including The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God, The Doctrine of God, The Doctrine of the Word of God, The Doctrine of the Christian Life, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Christian Belief, Concise Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Christian Belief, A History of Western Philosophy and Theology, and Apologetics: A Justification of Christian Belief.

John M. Frame (BD, Westminster Theological Seminary; AM, MPhil, Yale University; DD, Belhaven College) is J. D. Trimble Professor of Systematic Theology and Philosophy, Emeritus, Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando. He is the author of many books, including the four-volume Theology of Lordship series, and previously taught theology and apologetics at Westminster Theological Seminary (Philadelphia) and at Westminster Seminary California.

- Scripture refers to “the Ten Commandments” (see Ex. 34:28; Deut. 4:13; 10:4), but never numbers the individual commandments. There are several different numbering systems. Roman Catholics and Lutherans combine the commandment to have no other gods with the commandment forbidding graven images into one commandment, calling that the first, and then split the prohibition of coveting into two: the ninth being about coveting your neighbor’s house, and the tenth being about coveting his wife, servants, or animals. I will be using the form of numbering common in the Reformed tradition, which sees the prohibition of other gods as the first, the exclusion of idols as the second, and the prohibition of all coveting as the tenth. Choice of a numbering system is not of much theological importance. The Roman-Lutheran system does give less prominence than the Reformed to the command concerning the worship of idols, reflecting a difference in theological emphasis that I will discuss under the second commandment. Nevertheless, their numbering system may be correct. The blessing and curse in Ex. 20:5b–6 appropriately attach to all of verses 3–5a, not just to verses 4–5a. On the other hand, the Roman-Lutheran division of the prohibition of coveting into two commandments is quite implausible. Another possibility is that the references in Ex. 34:28 and elsewhere include the preface of 20:2 as the first. That verse is not, of course, a commandment, but the Hebrew term translated “commandment” in Ex. 34:28 is dabar, “word.” In the traditional Jewish numbering, verse 2 is combined with verse 3 to constitute the first word, and the other commands are numbered as in the Reformed view. But if verse 2 is taken to be the first word, then verses 3–6 could be taken together as the second, and from then on the numbering would work as in the Reformed tradition. That seems to me to be the most likely alternative, but I will follow the standard Reformed numbering.

- WLC, 98.

- Traditionally, it has been held that the two groups of four and six commandments are the “two tablets” of the original edition (Ex. 31:18; 32:15; 34:1, 4, 29; Deut. 4:13; 5:22; etc.). But I agree with Meredith G. Kline’s argument that the two tablets each included all ten. In the Near Eastern treaties, two copies were made, one for the sanctuary of the great king and one for the sanctuary of the vassal king. In Israel, however, there was only one sanctuary, and both copies were placed there. See Kline, The Structure of Biblical Authority (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1972), 113–30.

- Luther’s Small Catechism, I, A.

- Luther’s Large Catechism is even more elaborate, but its answers, here and elsewhere, are sermonic essays on the text. The Larger Catechism, on the other hand, is a list of mandatory applications, without sermonic discussion. It is more like a legal document.

- Or “bold and curious searching into his secrets”? Or “vain credulity”? Or “charging him foolishly for the evils he inflicts on us”?

- Do not confuse this use of the term cultic with its use to designate heretical and non-Christian sects.

- For a more elaborate account of worship in Scripture, see my Worship in Spirit and Truth (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1996).

- For additional references, see DG, 679–80.

- Recall my argument in chapter 19 that love gives a positive thrust to biblical ethics, even though Scripture often states its commands negatively.

- Hence there is the frequent biblical parallel between our covenant with God and the marriage covenant. See chapter 19 and our later discussion of the seventh commandment.

- The Syrian general Naaman, healed of leprosy by Yahweh, determined from that time forward to worship only the God of Israel. But he told the prophet Elisha that he would still be required to escort the king of Syria into the temple of Rimmon for worship. The king would lean on his arm, forcing him into a bowing position! He asked pardon in advance for this, and Elisha appears to have granted it (2 Kings 5:1–19). In these bows, Naaman would not actually be worshiping Rimmon, for worship is a matter of the heart. But the physical act of bowing is something that both Naaman and Elisha took seriously: it requires a pardon, divine forgiveness.

- “Mammon,” in Matt. 6:24 and Luke 16:9–13 in some translations, simply means “wealth” or “money.” But Jesus personifies it, as if it were the name of a god, enhancing the allusion to the first commandment.

- Vern S. Poythress, The Shadow of Christ in the Law of Moses (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1995), 141–42.

- For the meaning of holiness, see DG, 27–29. On p. 28, I define it as “God’s capacity and right to arouse our reverent awe and wonder.”

- Tremper Longman III, Immanuel in Our Place: Seeing Christ in Israel’s Worship (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2001).

- Poythress, The Shadow of Christ in the Law of Moses, 81–82.

- Ibid., 83. Poythress cites Gordon J. Wenham, The Book of Leviticus (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1979), 21.