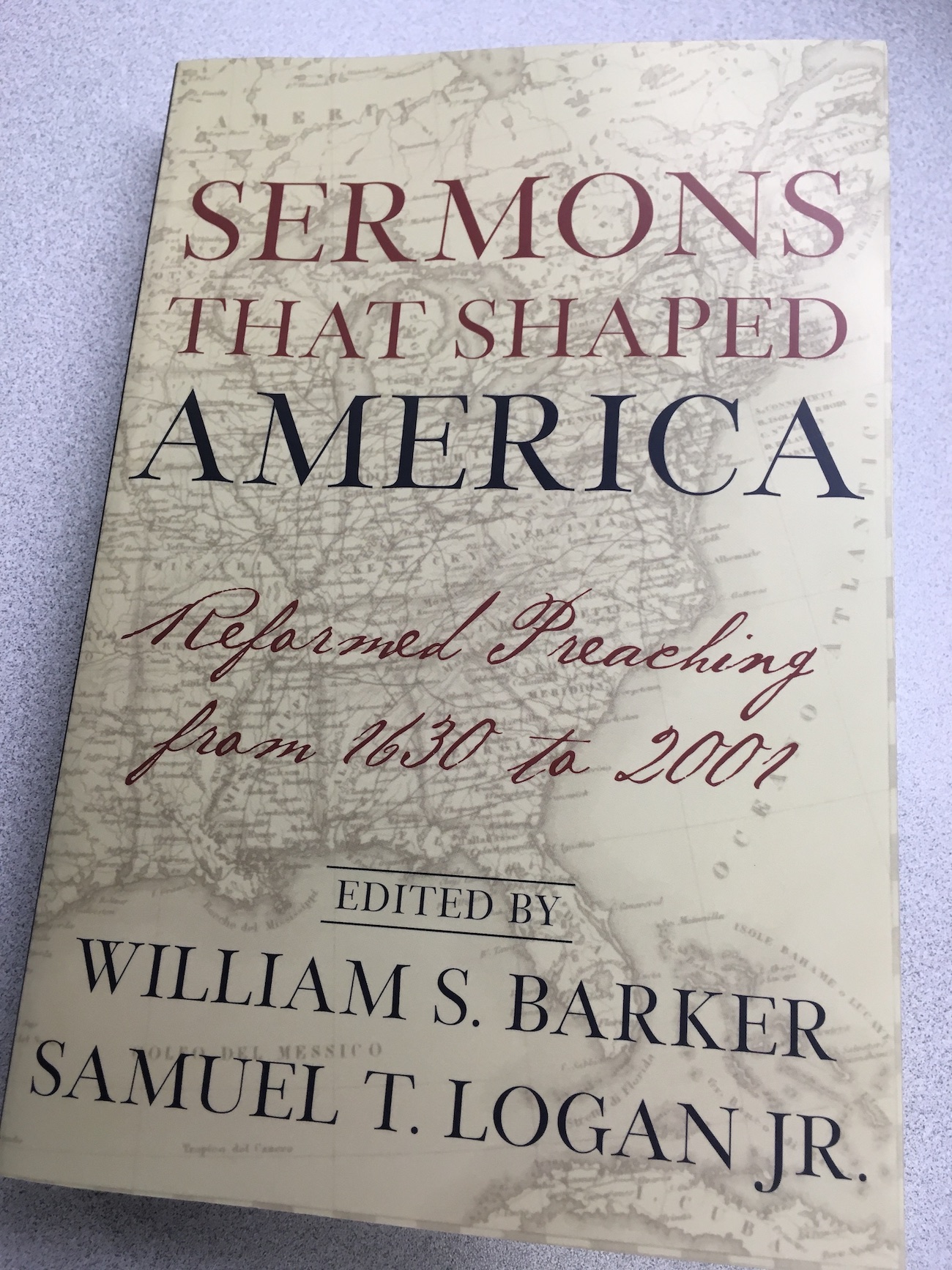

Sermons That Shaped America: Reformed Preaching from 1630 to 2001 edited by William S. Barker & Samuel T. Logan Jr.

Preface

“How shall they hear without a preacher?” the apostle Paul asks in Romans 10, part of his argument for the critical importance of the “foolishness” of preaching.

Without a doubt, the church stands or falls, grows or dies according to the quality of the weekly diet that it is fed. From the prophetic orations of the Old Testament to and beyond the missionary sermons of the  New, what the people of God are toldmatters. The use of words (and use of the symbolism of God’s Word) has always been and will always be a uniquely formative activity in the life of the church.

New, what the people of God are toldmatters. The use of words (and use of the symbolism of God’s Word) has always been and will always be a uniquely formative activity in the life of the church.

And not just in the church.

To the degree that the church affects the world in which God has placed it, to the degree that the worldview of the church shapes the society in which the church functions, to that very degree what is said in the pulpit on Sunday morning produces direct consequences, some intended and some not, in the entire community on Monday, Tuesday, and the rest of the week.

Harry Stout has probably stated it best in his study of “The New England Soul.” And while his comments apply most directly and most clearly to an earlier American culture, they unquestionably apply as well to a modern culture in which thousands listened to a sermon just days after and blocks from the site of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. These are Stout’s words:

The sermon stood alone in local New England contexts as the only regular (or at least weekly) medium of public communication. As a channel of information, it combined religious, educational, and journalistic functions, and supplied all the key terms necessary to understand existence in this world of the next. 1

How do we understand existence in a world where terrorism is as real as an airline boarding pass? Or in a world where human beings are bought and sold as slaves? Or in a world where another nation, the nation from which we came, seems bent on destroying us? Or in a world where we are given the opportunity to start a Holy Commonwealth from scratch?

And when all the cultural and ethical and technological changes of the past 380 years are amassed, how dowe understand existence in the next world? To what degree do the societal changes we are experiencing affect our understanding of the next world?Arethere any unchanging words to be spoken in or to this changing world?

Sermons preached in American pulpits from 1630 to 2001 still provide answers to these seven questions. And some of those answers singularly shaped the United States as a nation.

One of the values of this collection of sermon, therefore, is historical. Each of them played a unique and critical role in what America has become. Lengthy volumes such as Ola Winslow’s Meetinghouse Hilland Alan Heimert’s Religion and the American Mind and Bernard Bailyn’s The Ideological Origins of the American Revolutionand Colleen Carroll’s The New Orthodoxytrace the historical impact of religious ideas on American society. We have tried to briefly suggest the specific historical impact of each sermon included here and have frequently suggested other sources that can be used to pursue in more depth the themes introduced by individual sermons.

But there is even more there than matters of historical interest.

Precisely because the preachers of these sermons believed that there is an unchanging Word from God and precisely because they sought to faithfully speak that Word into the changing world they faced, what they said matters greatly to those who, today, continue to believe in the power and sufficiency and authority of that Word.

No, of course these sermons are not inspired. Some of them will even seem foolish to modern readers (as they did to some who heard them when they were first preached). But God’s Word, when faithfully preached, never returns to Him void (Isa. 55:11). Sometimes, in fact, the preaching of that Word produces thirtyfold, or sixtyfold, or hundredfold results (Matt. 13:23). When sermons produced results like that in earlier generations (as these appear to have done), they may do the same in ours.

And that is precisely our prayer!

—Samuel T. Logan

1. Harry Stout, The New England Soul: Preaching and Religious Culture in Colonial New England (New York: Oxford University, 1986), 3.

Table of Contents

- John Cotton (1584—1652): “God’s Promise to His Plantation” (2 Sam. 7:10)

- John Winthrop (1588—1649): “A Model of Christian Charity”

- Cotton Mather (1663—1728): “The Loss of a Desirable Relative, Lamented and Improved” (Ezek. 24:16)

- Jonathan Edwards (1703—58): “The Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God” (1 John 4:1)

- Gilbert Tennent (1703—64): “The Danger of an Unconverted Ministry” (Mark 6:34)

- Jonathan Mayhew (1720—66): “Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to the Higher Powers” (Rom. 13:1—7)

- Ezra Stiles (1727—95): “The United States Elevated to Glory and Honor” (Deut. 26:19)

- Archibald Alexander (1772—1851): “A Sermon Delivered at the Opening of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States” (1 Cor. 14:12)

- Asahel Nettleton (1783—1844): “Professing Christians, Awake!” (Rom. 13:11)

- James Waddel Alexander (1804—59): “God’s Great Love to Us” (Rom. 8:32)

- Benjamin Morgan Palmer (1818—1902): “The Headship of Christ over the Church” (Eph. 1:22—23)

- John L. Girgardeau (1825—98): “Christ’s Pastoral Presence with His Dying People” (Ps. 23:4)

- Geerhardus Vos (1862—1949): “Rabboni!” (John 20:16)

- Clarence Edward Macartney (1879—1957): “Shall Unbelief Win? An Answer to Dr. Fosdick”

- J. Gresham Machen (1881—1937): “Constraining Love” (2 Cor. 5:14—15)

- Francis A. Schaeffer (1912—84): “No Little People, No Little Places” (Ex. 4:1—2; Mark 10:42—45)

- James Montgomery Boice (1938—2000): “Christ the Calvinist” (John 10:27-19)

- Timothy Keller (1950—): “Truth, Tears, Anger, and Grace” (John 11:20—53)

Comments