Biblical Christianity makes two indisputable affirmations, yet not without generating fierce controversy. First, God controls in some sense all that transpires in time, space, and history, including the course of human lives. Second, human beings are responsible moral agents who freely choose the direction that their lives take. Our ability to make meaningful choices that impact history as it unfolds is what separates us from every other creature.[1] On the surface, these two truths appear to be in conflict with each other. How can God direct the path of human history and yet humans remain free to choose their own course of action?

This question has plagued philosophers and theologians throughout the ages. The problem perplexes us no less today. Even popular culture has tuned in to the vexing question. Anyone who has watched the Matrix trilogy or Groundhog Day is confronted with daunting notions about free will and whether events are predetermined. The comic strip Foxtrot by Bill Amend tackled the matter with a dry wit befitting the ponderous nature of the subject. In the first frame of a strip composed in 2003, the main protagonist of the comic, ten-year-old Jason Fox, holds a football over his head. He calls out to his best friend, Marcus Jones, to “go deep.”[2]

Marcus deadpans, “How can free will coexist with divine preordination?”[3]

In the next frame, Jason silently ponders the question. In the third frame he replies, “Too deep.”[4]

Marcus then alleviates the moment with lighter fare: “If Batman died, would the Joker be happy?”[5]

Is Reconciliation Possible?

Since free will and divine sovereignty seem irreconcilable, one or the other is usually denied or limited in some degree. Historically, some Christians say that God has purposely limited his sovereignty in order to uphold man’s free will. This is most often associated with Arminianism and the teachings of the theologian Jacob Arminius (1560–1609). Other Christians have emphasized God’s sovereign determination of what transpires while either limiting human freedom or denying it altogether. This is generally associated with Calvinism, a term derived from the Protestant Reformer John Calvin (1509–64). Of course, both views date to the early history of the church.[6]

The matter seems straightforward. Either man has a free will that limits God’s sovereignty or God is absolutely sovereign and man is not really so free. But is it possible to somehow reconcile God’s sovereignty with human freedom? It is my quest to answer that question in the affirmative.

This is no easy task, for several reasons. First, the issue has generated no small amount of controversy within the history of the church, including the present. Second, confusion is often generated by the controversy because of caricatures on both sides of the debate. Third, the issues can get complicated, especially because of the apparent contradictory nature of the two basic propositions. Fourth, the claim that we have free will is usually assumed to be true and its meaning self-evident. But if pressed, few are able to articulate a definition. The idea of free will becomes muddled very quickly. Finally, Scripture itself doesn’t provide straightforward answers to questions about free will.[7]For that reason alone, one must approach the subject with great care.

My purpose is to try to clear up some of the murkiness that is commonplace and to provide biblical answers to the questions that free will raises. Most Christians have no problem accepting God’s control over the big picture of history. When it comes to God’s preordaining our actual choices, however, we often entertain a different perspective. Many assume that God’s actions have little bearing on our personal choices. We like to reserve a degree of autonomy for ourselves. God’s sovereignty provokes nightmares “that we are like puppets being jerked around against our wills by a malevolent master puppeteer.”[8]

For many, to deny free will is anathema—we have no choice (!) but to believe in free will. This is understandable. It appears intuitively obvious that we make our own independent choices.[9] They are usually made unhindered and seemingly apart from any outside causes other than our own freedom to choose. This is where confusion sets in. Many readily accept that God chooses us for salvation and directs our lives for his purposes, but don’t we freely choose what we want as well? How can both notions be true? The burden of this book is to answer such questions.

Why Bother?

Does it really matter what one believes about such a contentious subject? Why is it so important? Well, it certainly generates lively debate, but there are reasons why believers need clarity about the matter. A biblical view of divine sovereignty and human freedom highlights a host of important matters in the Christian life. It helps us in the following ways:

- Sorting out God’s role and our role in matters of salvation.

- Making sense of how regeneration, conversion, and sanctification work.

- Understanding how we should engage in evangelism and discipleship.

- Building greater confidence in God’s providential purposes for both history and our individual lives.

- Navigating crucial questions about the existence of evil and whether God or man or even Satan is responsible for it.

The questions can be quite personal:

- If God determines the course of events in my life, how can I be responsible for my actions?

- How can I have a meaningful relationship with God? Doesn’t his sovereignty undermine my choice to freely love him?

- Why should I pray, if God has already determined the future? Can my prayers change God’s mind? Do my choices have any bearing on the course of the future?

- Do God’s commands really matter? If he is sovereign, can’t I do whatever I want?

- Isn’t divine determinism—another way of speaking of God’s absolute sovereignty—really fatalism, so that it doesn’t matter what choices I make? Shall I resign myself to “what will be will be,” since I can do nothing about it?

- How can I know whether my choices are in or out of the will of God?

The questions are endless, and the unbridled speculation about the answers threatens to wreak havoc on our limited brain capacity.

I am not writing another book about the doctrine of predestination or the problem of evil and suffering. It will become necessary to touch on these topics, but full treatments of them are to be found elsewhere.[10] Yet few books treat the issue of free will exclusively, especially from a distinctively biblical perspective. Older treatments on the topic are so ponderous that they leave the average reader bewildered—works such as Augustine’s On Free Choice of the Willand Martin Luther’s The Bondage of the Will. Other treatments of free will engage in discussing heavy philosophical concepts that make matters worse.

Compatibilism and Libertarianism

I approach this subject from what I believe the Scripture, rightly interpreted, teaches. Nonetheless, it corresponds historically to what Calvinism has taught. Furthermore, the approach taken here is often labeled compatibilism. Although the term compatibilism is part of the parlance of modern philosophical discourse on this issue, it accurately reflects what the great American colonial pastor and theologian Jonathan Edwards taught. He was the first to thoroughly articulate the ideas of compatibilism in his magisterial tome Freedom of the Will, written in 1754.[11] The common alternative view to compatibilism held among theologians is known as libertarianism, which is in no way related to the political ideology of the same name. This is the view held by Arminians and open theists.[12] This subject matter is not confined to the domain of theology. Secular philosophers engage in these discussions as well, and the viewpoints span a wide and complicated spectrum.[13] Generally, I will not concern myself with non-Christian viewpoints, even though some significant overlap in ideas occurs.

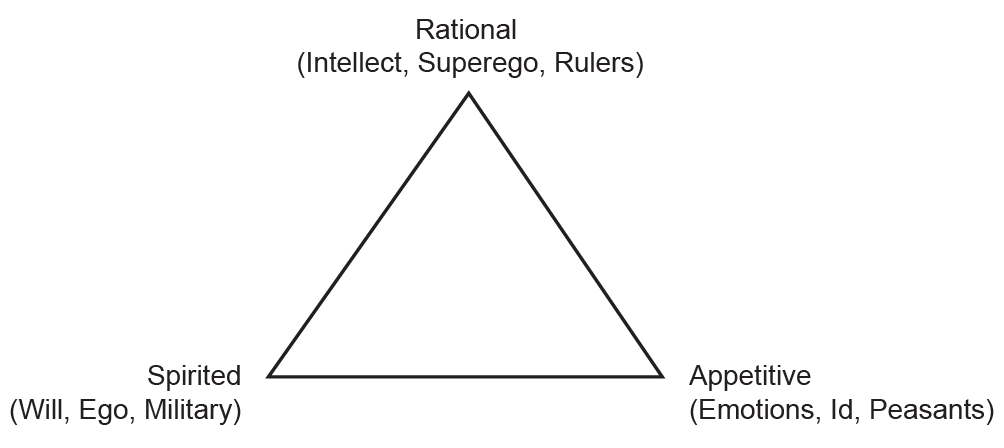

A distinctly biblical form of compatibilism holds that there is a dual explanation for every choice that humans make. God determines the choices of every person, yet every person freely makes his or her own choices. Thus, divine sovereignty is compatible with human freedom and responsibility. In this model, people are free when they voluntarily choose what they most want to choose as long as their choices are made in an unhindered way. In either case, what people actually choose, whether hindered or not, is determined by a matrix of decisive causes both within and without. Biblical compatibilism says that our choices proceed from the most compelling motives and desires we have, which in turn is conditioned on our base nature, whether good or evil. The more voluntarily and unconstrainedly our choices are made, the more freedom and responsibility we have in making them. Sometimes this is called the freedom of inclinationbecause a person is always inclined to make particular choices.

Conversely, libertarianism teaches that free will is incompatible with divine determinism (i.e., God’s meticulous decreeing of all things), since this undermines human freedom and responsibility. It should be noted that Arminians do not espouse the incompatibility of human freedom with divine sovereignty. Rather, they hold that divine sovereignty is exercised so that God does not causally determine human actions.[14] Libertarian freedom of choice comes about when we have the ability to choose contrary to any prior factors that influence our choices, including external circumstances, our motives, desires, character, and nature, and, of course, God himself. If these prior influences decisively determine choices, then the freedom and responsibility of those choices are hindered. God is in control of history, but he exercises that control so as not to interfere with man’s free will. Libertarian free will is often called the freedom of contrary choice.

If the libertarian definition of free will is correct, then God is limited in his sovereignty. On the other hand, if the compatibilist view of man’s will is correct, then it not only is compatible with a robust view of divine sovereignty, but also preserves human freedom and responsibility. I will seek to show how the libertarian view of free will falls short of making sense of human experience and what Scripture teaches. Throughout the book, the main object of my critique is classic Arminianism and its appropriation of libertarian arguments. In contrast, I will devote the larger part of the book to defending a compatibilist perspective on the human will, which I believe is more faithful to Scripture and makes far better sense of our actual experience.

In making the case for compatibilism and against libertarianism, I run up against some unavoidable philosophical concepts and arguments. But my primary goal is not to assess all the complex philosophical arguments, but to show that a broad compatibilist framework better fits the scriptural evidence. The Bible is our decisive authority for judging ultimate truth claims.[15]

The organization of this book is as follows: Chapters 1 and 2 will lay out the libertarian viewpoint and its shortcomings. Chapter 3 will examine what the Bible teaches about God’s absolute sovereignty in determining human affairs, including our choices. This chapter precedes the overview of compatibilism in chapter 4, since God’s sovereignty is foundational to understanding biblical compatibilism. Chapters 5 and 6 will look at two prominent sets of compatibilistic patterns in the Bible to demonstrate the truth of this perspective. The chapters that follow will seek to flesh out the compatibilist view of the human will, freedom, and responsibility. Along the way, I will discuss how this perspective makes sense of many theological and practical issues that affect our everyday lives. The book is designed to facilitate further study of the topic. With that in mind, I close each chapter with a chapter summary and study questions. Most chapters also include a glossary of terms[16] and resources for further study. There is also a full glossary of terms at the end of the book, as well as two appendices. The first appendix is a chart that compares libertarian beliefs with compatibilist beliefs. The second appendix is a review of Randy Alcorn’s recent book hand in Hand: The Beauty of God’s Sovereignty and Meaningful Human Choice, which tackles the same topic. Although Alcorn promotes a compatibilist position, I seek to point out that his perspective differs considerably from traditional biblical compatibilism.

To sort through all the thorny questions and befuddled ideas that surround this topic is daunting, but the rewards are worth the effort. When we enhance our understanding of God’s role and our own roles as his plan unfolds for history and our personal lives, it gives us confidence and hope that God is good and wise and powerful and that our choices have meaning and purpose. We are a vital part of what he does in the world. Our choices matter, and what makes this true has everything to do with the manner in which his sovereignty manifests itself in our lives. I trust that this book will be a faithful guide in understanding this truth.

Glossary

Arminianism. A theology associated with the teachings of Jacob Arminius (1560–1609). Arminianism teaches five basic ideas. First, God has predestined to save those whom he foreknows will exercise faith in Christ. Second, Christ’s death was an atonement for all mankind regardless of who believes on Christ for salvation. Third, humans in their natural state do not have free will or the capacity for saving faith. But, fourth, God has supplied prevenient grace to all humans so that they can recover free will and exercise saving faith. This prevenient grace enables them to either cooperate with God’s saving grace or resist it if they choose. Fifth, the grace of God assists the believer throughout his life, but this grace can be neglected. Subsequently, the believer can incur the loss of salvation.

Calvinism. A theology that embraces a broad spectrum of ideas associated with the teachings of the Protestant Reformer John Calvin (1509–64). Calvinism, however, is often identified by the five points of Calvinism, traditionally represented by the acronym TULIP. The T stands for total depravity, which indicates that humanity is in bondage to sin. The U stands for unconditional election, which indicates that God chooses people for salvation wholly apart from anything they do. The L stands for limited atonement, which indicates that Christ’s death secured atonement only for the elect. The I stands for irresistible grace, which indicates that God draws chosen sinners to salvation irresistibly. The P stands for perseverance of the saints, which indicates that the elect will certainly persevere in their salvation until the end.

compatibilism. The biblical view that divine determinism is compatible with human free will. There is a dual explanation for every choice that humans make. God determines human choices, yet every person freely makes his or her own choices. God’s causal power is exercised so that he never coerces people to choose as they do, yet they always choose according to his sovereign plan. People are free when they voluntarily choose according to their most compelling desires and as long as their choices are made in an unhindered way. While God never hinders one’s choices, other factors can hinder people’s freedom and thus their responsibility. Furthermore, moral and spiritual choices are conditioned on one’s base nature, whether good or evil (i.e., regenerate or unregenerate). In this sense, one is either in bondage to his or her sin nature or freed by a new spiritual nature. See also soft determinism.

divine sovereignty. The biblical doctrine that God controls time, space, and history. Calvinists usually hold that God meticulously determines all events that transpire, including human choices. Arminians teach that God limits his sovereign control of events, giving humans significant freedom of choice, which is defined as libertarianism. See also determinism.

free will (free agency). The idea that humans are designed by God with the capacity for freely making choices for which they are responsible. Most Calvinists and Arminians agree that some kind of free agency is necessary for moral responsibility. But each branch of theology defines it differently. Arminians embrace a libertarian notion of free agency. Many Calvinists embrace a compatibilist notion of free agency. See also compatibilism and libertarianism.

human responsibility. See moral responsibility.

libertarianism. The view that free will is incompatible with divine determinism (i.e., God’s meticulous decreeing of all things), which undermines human freedom and moral responsibility. God’s sovereignty is exercised so that he does not causally determine human actions. Freedom of choice comes about when one has the ability to choose contrary to any prior factors that influence the choice, including external circumstances, one’s motives, desires, character, and nature, and, of course, God himself. If these prior influences decisively determine choices, then the freedom and responsibility of those choices are undermined.

moral responsibility. Humans’ culpability for their moral choices. A person who does good deserves praise or reward. A person who does evil deserves blame or punishment. Most Calvinists and Arminians believe that some kind of human freedom is necessary for moral responsibility. Also termed human responsibility.

Resources for Further Study

F. Leroy Forlines, Classical Arminianism: A Theology of Salvation (Nashville: Randall House, 2011). A very readable defense of Arminianism.

Roger E. Olson, Arminian Theology: Myths and Realities (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006). One of the better defenses of Arminianism.

R. C. Sproul, Chosen by God (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 1986). A classic defense of the Calvinist view of election.

R. C. Sproul, Willing to Believe: The Controversy over Free Will (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1997). A survey of the debate over free will in the history of the church.

David N. Steele, Curtis C. Thomas, and S. Lance Quinn, The Five Points of Calvinism (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2004). An excellent source for Scripture’s defense of the five points of Calvinism.

Sam C. Storms, Chosen for Life (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2007). An engaging defense of the Calvinist view of election. Also treats libertarian and compatibilist views of free agency.

Jerry L. Walls and Joseph R. Dongell, Why I Am Not a Calvinist (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004). A popular defense of Arminianism and critique of Calvinism.

Scott Christensen is the author of What about Evil? A Defense of God’s Sovereign Glory and What about Free Will? Reconciling Our Choices with God’s Sovereignty.

Scott Christensen (MDiv, The Master’s Seminary) worked for nine years at the award-winning CCY Architects in Aspen, Colorado: several of his home designs were featured in Architectural Digest magazine. Called out of this work to the ministry, he graduated with honors from seminary and now serves as the associate pastor of Kerrville Bible Church in Kerrville, Texas.

[1] Mark R. Talbot, “All the God That Is Ours in Christ,” in Suffering and the Sovereignty of God, ed. John Piper and Justin Taylor (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2006), 56.

[2] FOXTROT © 2003 Bill Amend. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL UCLICK. All rights reserved.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.; also reprinted in Peter J. Thuesen, Predestination: The American Career of a Contentious Doctrine (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 222.

[6] For the history, see R. C. Sproul, Willing to Believe: The Controversy over Free Will (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1997).

[7] John S. Feinberg, No One Like Him (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2001), 679.

[8] Gerhard O. Forde, The Captivation of the Will: Luther vs. Erasmus on Freedom and Bondage (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 31.

[9] Jerry L. Walls and Joseph R. Dongell, Why I Am Not a Calvinist (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004), 104; Clark H. Pinnock, “Responsible Freedom and the Flow of Biblical History,” in Grace Unlimited, ed. Clark H. Pinnock (Minneapolis: Bethany House, 1975), 95.

[10] Good accessible treatments of the doctrine of predestination include R. C. Sproul, Chosen by God (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 1986); Sam C. Storms, Chosen for Life (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2007); and David N. Steele, Curtis C. Thomas, and S. Lance Quinn, The Five Points of Calvinism (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2004). Good accessible treatments of suffering and evil include chapters 6 and 7 in John M. Frame, Apologetics to the Glory of God(Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1994); D. A. Carson, How Long, O Lord? Reflections on Suffering and Evil (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2006); and Joni Eareckson Tada and Steven Estes, When God Weeps (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1997). For a more advanced philosophical and theological treatment, see John S. Feinberg, The Many Faces of Evil: Theological Systems and the Problem of Evil (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2004).

[11] Jonathan Edwards, The Freedom of the Will, vol. 1 of The Works of Jonathan Edwards, ed. Paul Ramsey (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1957). On Edwards as a compatibilist, see Paul Helm, John Calvin’s Ideas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 164–71; Paul Helm, “Edwards and the Freedom of the Will,” available at http://paulhelmsdeep.blogspot.com/2011/02/edwards-and-freedom-of-will.html. Compatibilist beliefs are not monolithic. One need not follow all that Edwards taught to be a compatibilist.

[12] Open theism is a radical brand of Arminianism that has been rejected as unorthodox by Calvinists and many Arminians. Open theists virtually deny God’s sovereignty as clearly spelled out in Scripture, including his omniscience and other attributes accepted by orthodox Christianity. See the treatment of this movement by Bruce A. Ware, God’s Lesser Glory: The Diminished God of Open Theism (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2000); John M. Frame, No Other God: A Response to Open Theism (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2001).

[13] See Robert Kane, A Contemporary Introduction to Free Will (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005); Joseph Keim Campbell, Free Will (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2011).

[14] Steve W. Lemke, “A Biblical and Theological Critique of Irresistible Grace,” in Whosoever Will: A Biblical-Theological Critique of Five-Point Calvinism, ed. David L. Allen and Steve W. Lemke (Nashville: B&H Publishing Group, 2010), 150–51.

[15] Many philosophers believe that the arguments for various views on free will and determinism have reached an impasse. But philosophical argumentation is not our final recourse—Scripture is (John 17:17; Col. 2:8).

[16] Most italicized terms in each chapter’s glossary are cross-references to other entries, either in the chapter glossary or in the full glossary at the end of this volume.